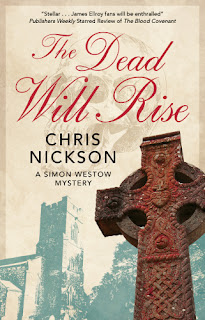

Chris Nickson will be familiar to So19 readers from our interviews on two of his Tom Harper novels, Two Bronze Pennies and The Molten City. The publication of his fifth Simon Westow mystery offers the chance to speak with him about a series set in the same city, but at a quite different time. Chris's first mystery series features Richard Nottingham, Constable of Leeds in the 1730s. Two books about 1950s private enquiry agent Dan Markham are also set in Leeds, as are the Tom Harper books and two Lottie Armstrong novels. It's clear that, as Chris says, Leeds is in his DNA. Find out more about Chris on his website (which includes some great background materials on historic Leeds as well as info on all of his books), Twitter page, and Instagram. Buy The Dead Will Rise on Amazon UK, Amazon US, and Bookshop. With thanks to Chris for his time, here's our chat.

I write historical crime novels, mostly set in my hometown Leeds. I've always written, it seems, and for a long time made my living as a music journalist (while living in Seattle and after) and writing quickie unauthorized celebrity bios. All an excellent education for a novelist, it seems.

My passion for Leeds history began when I lived abroad, and remains now I'm back where I grew up. Thankfully.

Q. We’ve spoken previously about your Tom Harper mysteries, the first of which opens in the 1890s. I’m excited to talk to you about your Simon Westow novels, which are set seventy years earlier. To start, tell us a little about the inspiration for this series. How and when did the idea for the series and its protagonist arise?

Strangely, the idea rose from a phrase I came across in Robert Hughes' book, The Fatal Shore, about transporting convicts to Australia. The “hanging psalm.” I loved that. I'd been considering something with a thief-taker, and from there it fell into place.

Q. Talk a little about Leeds in the 1820s. Why did you choose to focus on that particular decade—what possibilities for mysteries, or just for fictional tensions, did it offer?

The 1820s saw the Industrial Revolution in full swing here. Manufactories and workshops all over town. The start of the machine age, when there was plenty of innovation. But in many ways it was like the London Dickens described. Awful poverty, plenty of street children, starvation. That offers plenty of possibilities. A wider gap between rich and poor than in the time of my Richard Nottingham books, and a larger population—from six of seven thousand to well over 30,000. A place where faces were easily lost. It marked a good mid-point between Richard Nottingham and Tom Harper. It was also a time before Leeds had a real police force, just the night watch, ward inspectors and a chief—not good or efficient.

Q. Could you talk about one or two of the places in Leeds—streets, buildings, other structures—that still exist from this period and helped you imagine the novels’ world?

There's so much in the way to streets that have remained unchanged for centuries in the city centre, at least in the layout, if not the buildings. Commercial Street was built at the start of the 1800s, and if you look up, you can see what the buildings were like, including the Leeds Library, the oldest subscription library in the UK, which has been in the same spot since 1808. And tiny streets like Green Dragon Yard and Butts Court still exist. Pitfall remains, a very short block running from The Calls down to the river like Leeds Bridge. That history is still all around me.

Q. Simon Westow, your protagonist, is a “thief-taker.” Could you talk a little about that job and how its characteristics—for example, the focus on missing property, the contact with those wealthy enough to pay personally for its return, or the lack of formal organizational structures that were instituted in later policing—open up story possibilities?

Thief-takers were real, pretty much a cross between bounty hunters and private detectives in a country that didn't have an organized police force—outside the Bow Street Runners in London, who were the Scotland Yard of their day. Towns and cities had the night watch, led by a few inspectors and a constable. But the pair was terrible, so the quality was poor. Plenty of capital offences—around 200 on the statute books, although many of those convicted receive reprieves.

When someone was robbed, or had a theft, they could put an advertisement in the local paper, offering a reward for the return on the items. A thief-taker would start hunting. If successful, they'd receive a fee. If the item didn't meet the threshold for a felony prosecution, the victim could take the offender to court at their own expense. No real incentive to pursue that.

A number of thief-takers worked with thieves and developed a racket. Inevitable, really. Some ended up in prison and transported themselves. They existed in that murky area between crime and the law.

Q. A number of strong mystery series set in Regency England focus on aristocratic sleuths and milieus. In contrast, you gave both Simon Westow and his assistant Jane painfully insecure and impoverished backgrounds; in addition, the series as a whole explores the poverty and inequities of this period with searing vividness. Talk to us about that decision and/or task.

I know nothing of the aristocracy or those with money. Leeds had a very small core of what might be called society, but that was focused more in the county, the rural areas, rather than a smoky, stinking town.

I've always related more to the have-nots; I'm not sure why. Simon is a self-made man, living off his wits after a workhouse childhood. He understands poverty, he's lived it. It's natural that his sympathies would be with the poor and helpless. This was a time when the government was fearful. They passed the Six Acts, they'd clamped down on the Luddites, there had been the Cato Street conspiracy.

Yet at the same time, there was an early commission into the way children were treated in factories. Spoiler: badly. Began work aged 6, worked 12 hours and more 6 days a week, were beaten and abused. Simon had worked his way up, but never forgotten where he began.

My character Jane was raped by her father when she was eight, kicked out by her mother who'd rather have the security of a husband's wage. Learned to survive on the streets, with all that hardness that takes. These days we'd say she's on the spectrum, but she's learned to deal with things in her own way So she, too, has her sympathies.

Q. Simon’s assistant, Jane, is complex and fascinating. She’s as capable and resourceful as Tom Harper’s wife Annabelle, to name another strong woman in your writing, yet the two are also strikingly different. Could you talk about her character and how it’s developed?

I don't know where Jane came from, but then I don't know how Annabelle appeared, either. I prefer to think I'm channeling them rather than creating them. The North has strong women, I've seen them all my life, so maybe it's natural that the characters are that way. In her own fashion, my mother was strong. Jane is extreme, more out of circumstance than anything. With a shawl over her head, she disappears into a crowd, she can follow without being seen. In a way, that's a comment on how society sees women, even today. But also that the shawl was ubiquitous for working-class women.

In the books, Jane has finally found a home with Mrs. Shields, an old woman who lives in a semi-hidden place, an oasis of sorts, an idyll. She can finally relax and open up. She's learned to read and write, and she's devouring books. She'd learning numbers, things we take for granted, but weren't back then. She's growing up, yet still as deadly as before when she needs to be. I won't say more because I don't want to give too much away.

But, like Annabelle in the Tom Harper books, she's the linchpin of the series. She's the one who has my heart.

Q. The gripping plot of the just-published latest installment, The Dead Will Rise—the recipient of another of your well-deserved starred reviews from Publishers Weekly—finds a grieving father hiring Westow to locate a most unusual item. Could you give those who haven’t read it yet a bit of a preview?

Until the Anatomy Act of 1832, the supply of bodies for medical students to practice dissection were very, very limited, not even a dozen in a year. There was a demand from students and professors and medical schools and anatomy schools, so there was profit in supplying them. The recently dead were sometimes dug up and supplied. Sent in boxes on coaches, remarkably. It was a good, if gruesome, living for some. And pretty safe. Bodies weren't property, so if a body-snatcher was caught, it was only a misdemeanor, which meant a few weeks or months in prison, at most. People began taking precautions to keep their dead relatives in the ground. Some, like Burke and Hare in Scotland, went too far, and began murdering to increase the supply, but they were probably rare.

Simon is approached by a young engineer who's doing well to try and recover the body of a man who works for him. It's something new; he's used to dealing with things, not dead people. But as he starts to investigate, he learns that the gang have taken more than one body…bringing them to justice is going to been a brutal, deadly fight.

Q. Sadly for readers, your Tom Harper series is coming to a close with the next book…can we hope for more Simon Westows in the future?

I sincerely hope so. I'm awaiting a decision from the publisher on the next one, which they've indicated they'll take, though I've yet to hear a confirmation. It's a very dark book. Very dark indeed. And I have faint plans for another to follow that, too. I'll miss Tom and Annabelle and Mary, all of them, but it was time…Simon and Jane and Rosie still have a path ahead of them, I believe.

|

| Pitfall Street, Leeds by Tim Green, 2007. Creative Commons 2.0 image via Flickr.com |