Q. You’ve done so many interesting jobs! When did you begin writing fiction? What drew you to writing mystery novels rather than fiction in some other genre?

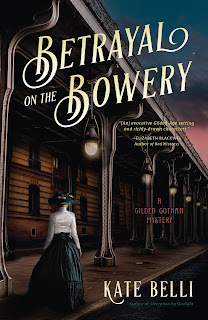

I started writing fiction some time ago, when I was in graduate school for art history. I think it began both as a reprieve from academic work and as a way to do something more creative with all the interesting history I was researching. When I started writing fiction, I was inspired by Julia Quinn’s Bridgerton books, and the Gilded Gotham series began its life as a Gilded Age historical romance, but I found it worked much better as a mystery. While there’s still a romantic subplot, I’ve become more drawn to writing murder than kissing.

Q. Your Gilded Gotham mystery series, which takes place in late 19th century New York, makes such rich use of its era and its setting. What drew you to this period and place as a basis for fiction?

My training as an academic in is American history and visual culture, so it was a bit of “write what you know.” I was working as a curator for the Brooklyn Historical Society (now the Center for Brooklyn History) when I envisioned this series, living and walking and working in New York City and its history every day. And as I was inspired by the Bridgerton series, I wanted to write something that held the same kind of glamour as the Regency period, but set in the US, and at a time when women had more freedom and opportunities. The Gilded Age into the Progressive era was a period of profound transition for women’s roles, where in a short time frame all kinds of things shifted—clothing became less restrictive, more professional and educational opportunities opened, more freedoms for women in general opened up, so it seemed a natural fit.

Q. Genevieve Stewart, your female protagonist, has her roots in New York high society but her sights on a future in investigative journalism, a career that was mostly deemed unsuitable for women during the years in which your novels are set. Was she inspired by any historical figure(s)?

I think “mostly unsuitable” is a good way to put it—women had been writing for newspapers and journals for a few decades by time the book takes place, though mostly about “women’s” issues. Genevieve is absolutely inspired by the famous Nellie Bly (the pen name for journalist Elizabeth Cochran), a historical figure considered to be the first female American investigative journalist. Bly did all kinds of amazing work for women, and is perhaps most well-known for having herself checked into a mental institution to report on the horrific conditions.

Q. In some ways, money gave women of this freedom: most notably perhaps, as captured in novels such as Edith Wharton’s The House of Mirth, freedom from the need to do the either backbreaking and/or soul-killing paid jobs that were available to females. Yet wealth and social position could also be incredibly limiting, confining well-heeled women to a narrow and highly codified range of choices and behaviors…in a sense, there’s a lot of money at stake when a society woman rejects those limits. For me, Stewart’s situation speaks of that paradox. Does that sound like a fair reading of your novels? Was it something you intended when you began to develop her character?

I do think this is a fair assessment, absolutely! And I did intend it that way, which is why I gave Genevieve an eccentric family, a suffragette mother and a progressive, socially liberal father; a family who was naturally part of the upper echelons of society due to their long-standing wealth, but who were also slightly outsiders from that society as they didn’t always follow those rigid social codes. A paradox is a great way to put it—and it is a challenge for Genevieve, as she tries to reject those norms while simultaneously having to exist within them.

Q. Your male protagonist, Daniel McCaffrey, has experienced both poverty and wealth. So he’s a liminal figure with connections to worlds that existed side by side yet were generally mutually exclusive. What led you do build his character this way?

I was interested in exploring the class tensions that were so rife in the time period, in that particular location, and in some ways Daniel embodies those tensions. I really wanted him to have experienced the Draft Riots, and for his immigrant experience and childhood to have shaped who he was and what he did with all that money once he inherited it—to press back against the extreme excess of the Gilded Age, be a part of it but also outside of it. Much like Genevieve—they’re both within and without of traditional upper-class society, in different ways.

Q. The Bowery district referenced in this novel’s title has undergone dramatic changes over the years. By the late 1970s, the early years of my own residence in Manhattan, it has declined into a neighborhood best known as a sort of Skid Row; these days it’s in a process (not entirely without controversy!) of gentrification. What interested you about this neighborhood circa 1890? What sources did you use to research its characteristics and possibilities?

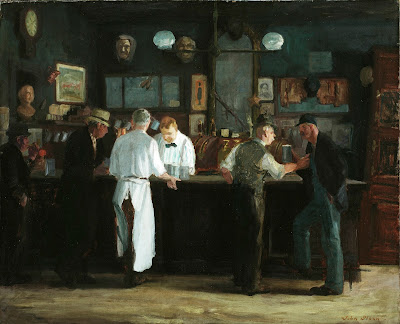

Ah, the Bowery in the 70s makes me think of Martha Rosler’s amazing photographic piece, The Bowery in two inadequate descriptive systems! It’s a fascinating area with such rich history. I leaned heavily on visual culture to help envision the Bowery area for this book, spending a lot of time with paintings and photographs that capture the neighborhood in the late 19th and early 20th centuries (John Sloan painted the area frequently). So many institutions have digitized their visual collections, which is wonderfully useful – the Museum of the City of New York is one I used a lot, as well as The New York Public Library. The book Low Life: Lures and Snares of Old New York by Lucy Sante (originally published under the name Luc Sante) was also a fabulous source of information I leaned on heavily.

Q. The Bowery dive you call Boyle’s Suicide Tavern, a strange and scary establishment that markets itself by giving out souvenir medallions to those who survive a night there, is one of the novel’s most memorable locations. Was it and/or those medallions inspired by a real place?

Yes! It was inspired by McGurk’s Suicide Hall, which was a real place at 295 Bowery, run by the gangster John McGurk. I fudged a little with the dates, the rash of suicides that gave the real hall its name occurred a bit later, in 1899 instead of 1889, but they did happen. And yes, according to the Bowery Boys podcast (another source I leaned on rather heavily for this book), the medallions stamped with McGurk’s face were handed out as souvenirs to those who spent time in the bar, which I embellished to being given out once someone survived the night.

Q. One of my other favorite Betrayal on the Bowery settings is your Garcia mansion, a once grand, now derelict home on the East River with mysteries that Stewart and McCaffrey must probe to solve the book’s intertwined puzzles. It’s at once a sort of haunted house and a place that has a lot of intricate logistics. Tell readers a bit more about it and its sources in real life if any?

Ah it’s one of my favorites as well! Yes, it’s absolutely based on a real place, the Casanova Mansion, also called Whitlock’s Folly, which was a grand mansion in Hunts Point in the Bronx. It was built in 1859, and demolished sometime around 1900. I don’t want to give too much of the book away, but several of unique logistics I describe in the book are absolutely true and existed in the real house, and were used for the same purpose as described!

Q. What are you up to, and working on, now?

I’m working on a few things right now; I’m in the editing stages of a new project, a contemporary stand-alone thriller. But I am also writing the last chapters of the third Gilded Gotham book, Treachery on Tenth Street, scheduled for an October 2022 release. It takes place almost immediately after Betrayal on the Bowery ends, just a few weeks later, during an intense heat wave in late summer 1889. A murderer is on the loose, targeting young women, specifically artists’ models and show girls. Daniel and Genevieve try to find the killer, a chase that takes them all over: the ultra-wealthy resort town of Newport, Rhode Island, artists’ colonies in Long Island, and the amusements of Coney Island. They’re doing all this while still grappling with their feelings over what happened at the end of Betrayal—my favorite thing about writing a series is continuing to engage with the characters over a good stretch of time. I hope there’s even more of these two to come, as it’s such fun to inhabit their world.

|

| Whitlock's Folly, later known as the Casanova Mansion courtesy of CorvusFugit.com |

|

| McGurk's Suicide Hall, courtesy of Curbed |

|

| McSorley's Bar, a more salubrious establishment than McGurk's (though one that didn't admit women until 1970); painting by John Sloan, 1912, in the collection of the Detroit Institute of the Arts |